| By Paul Crum As he prepared to enter a cab at the airport, the driver stopped him, saying, “I can take the colored gentleman, but you’ll have to wait on a white driver, sir.” “That was my welcome to Memphis,” Wallin remembered. As the new chaplain at the Memphis State Catholic Student Center, known then as the Neuman Center, the Paulist priest soon learned that campus life was not easy for the small, but increasing number of African-American students enrolled there. |

It had been only three years prior that African-Americans had been admitted to the university. When the institution was founded in 1912 as the West Tennessee State Normal School, only three requirements had to be met for admission: students had to be 16-years-old, an elementary school graduate and white.

According to “The University of Memphis Magazine,” Smith resigned his position in 1960.

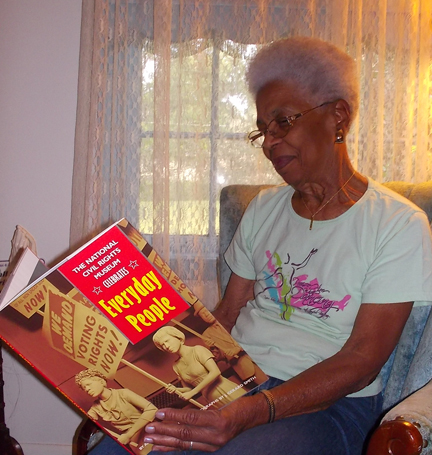

But a state university education was not an option for Earline Duncan, a retired Memphis schoolteacher who came of age during this time. For black students in the 1950s, who couldn’t afford the expense of living out of town, LeMoyne-Owen College was the only local option, even if the private school tuition was almost triple that of Memphis State.

Recalling the racial discrimination so prevalent in the decade, Duncan, 77, said, “We were accustomed to it. We didn’t know differently and it was bliss to the point that – since we couldn’t go, it didn’t register at that time.”

Her conversation with the son of the local Italian grocer, however, made the aspiring teacher realize the unfairness of the situation.

“When that little Italian boy told me he was only paying $60 a semester at the state school, while my parents were struggling to pay my $150 tuition, it made me angry,” Duncan said. “It resounded in my head that this was based solely on race.”

After Duncan graduated LeMoyne-Owen in 1959, enrollment at Memphis State would open up for her younger brother. Although the cost of his education was still substantially less than she had paid, African-American students were still isolated and ostracized by faculty and classmates.

Meanwhile, Father Ed Wallin was doing what he could to improve things at the Neuman Center.

“We expanded our dining room so the students would have another place to eat,” he said. And the black students were welcomed at our dances.”

He remembered an attractive French exchange student who had no problem dancing with boys of any race. But one of the Catholic chaperones observed the mixed race dancing and reported Wallin to his superiors.

“That’s when the John Birch Society got on my back,” he laughed. “They named me the number two communist in the city.”

As civil rights consciousness spread across college campuses, students following the lead of such leaders as the Rev. James Lawson, began small demonstrations at restaurants near the campus. Wallin recalled a daring rescue he made during one such incident.

“My students were picketing the Normal Tea Room on Highland,” he said. “The kids were pressed against the windows and the fraternity guys were beating them with clubs. The students were trying to block the blows with their little protest signs.”

Wallin drove his car up on the sidewalk and yelled at the students to get in.

“I must have had a dozen students in my little car,” he said, but we got away.”

At the suggestion of another pastor, Wallin joined the Air Force Reserve as a way of earning a salary. His campus minister position paid nothing, but the military was in desperate need of chaplains.

The uniform that came with the job also gave him another tactic for trying to integrate the neighborhood restaurants.

“I would recruit black and white Air Force officers to go with me to the restaurants,” he said, “but some of the owners we called on still refused.”

Out of desperation, Wallin asked University President Cecil Humpreys for help. He organized a meeting attended by Humpreys, local business owners and members of the NAACP. Soon things begin to change.

“One of the most popular restaurants was an Italian place over near the tracks on Southern run by a guy named Tony,” Wallin said. “I went in there with my little delegation and Tony said, ‘Is it time Father? I said ‘It’s time Tony.’”

Wallin would continue his civil rights work, walking with Dr. Martin Luther King in his famous March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, Miss. in 1966. As a campus priest he faced down violent counter protests while defending the freedom of speech of anti-war demonstrators.

Ironically, he would subsequently leave the Air Force, enlist in the Army Airborne and serve in the Vietnam War. Upon returning to the states, Wallin fell in love, left the priesthood, furthered his education and began a career counseling military veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder and other afflictions.

Wallin, now 85, remains active in the local peace and social justice community, and still works with veterans through organizations he helped found. Still, he recalls his time as a rabble-rousing campus minister as some of the best days of his life.

From the porch of the Catholic Student Center on Mynders Avenue, he points down Patterson and talks about riding along the street in the back of a pick-up truck demonstrating for freedom of speech.

“The fraternity boys were throwing things, but they didn’t throw anything at me,” he said. “Someone said, ‘Well it must be because you’re wearing your collar Father, but I pointed to my Memphis State jacket and said, no – it’s because they respect the tiger!’”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed